Going to start off a little technical this week. Don’t bail on me. After the technical, there will be some practical takeaways.

Adaptive leadership provides a model to think about and tackle complex problems. My study and understanding of adaptive leadership began for me at the Kansas Leadership Center (KLC), a place where the concept is deeply woven into the fabric of leadership development. KLC employs the adaptive leadership model as its foundational framework, aiming to empower leaders across Kansas (and the world) to navigate and address the complex challenges faced by organizations and communities. This model, a brainchild of Ron Heifetz and Marty Linsky of Harvard, offers a nuanced lens through which leadership can be understood and practiced, especially within the context of complex challenges[1].

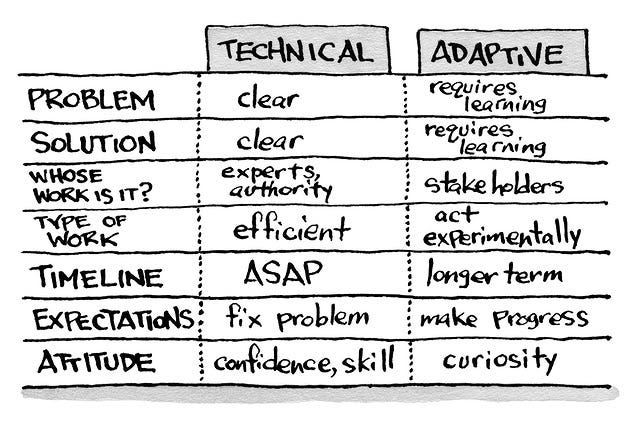

Central to the adaptive leadership framework is the distinction between adaptive and technical work, a differentiation that demonstrates how to approach a challenge. To bring this distinction to life, let’s look at some examples.

During a game, a player hurts their ankle very badly. The athletic trainer says he is out but is unsure of the extent of the injury.

What do you do?

Pretty simple…the player goes to the doctor (the expert) to find out what is wrong and a plan for recovery. If the doctor has trouble diagnosing the issue, an ankle specialist will likely be called. Why? Because the specialist is the expert. This is a technical problem with a technical solution. Something happens, you find the expert, and the expert gives you the solution. It can happen relatively quickly, and the problem can be fixed.

Playing out this example, let’s say the player that was hurt was a sophomore and it was a career ending injury. Further, this player was the hardest worker, the best player, well liked, and a team leader. The team now must deal with not only the disappointment of the hardship and disappointment their friend is facing but also how to reorient their team and move forward. They must find new team dynamics and ways of interacting, new ways of playing the game without their best player, new leaders must emerge, and the list goes on and on.

This is an adaptive problem. Learning is required, the team must work together, there will be trial and error, and it will take a while. Will the issue ever be totally fixed? Probably not because their best player is gone. But they can make progress every day.

Below is a helpful chart from the Kansas Leadership Center showing the elements of a technical vs. adaptive challenge. This has been an important resource for me in diagnosing what is going on and what is needed within different situations. While this frame might not be helpful to some coaches, it can help administrators understand what is going on and help lead coaches through different situations.

A common mistake leaders make is they diagnose adaptive challenges as technical. For example, the team chemistry is bad on a team and the coach thinks that one player is the issue. They want to kick the kid off the team and assume that all their problems will be solved. Could this be true? Sure. However, my experience tells me this reaction from a coach is often simplistic, avoids taking on the deeper issues within a program, and often creates more unrest and distrust in a program. It is treating an adaptive challenge as a technical issue.

The principles of adaptive leadership are particularly relevant in athletics, where leaders frequently encounter challenges that resist straightforward, technical solutions. On a broader scope, there are adaptive challenges that I hope we are taking on together as leaders within the realm of athletics.

· Creating a Healthier Sport Environment: This challenge extends beyond the implementation of wellness initiatives. It requires cultivating an ecosystem where athletes feel valued and supported, both on and off the field. Leaders must foster open conversations about mental health, encourage life balance, and create policies that reflect a commitment to holistic well-being.

· Developing Athletes' Identities Beyond Sports: Athletes often struggle with identity issues, particularly in highly competitive environments. Leaders must facilitate opportunities for athletes to explore and develop interests and skills outside of their sports, promoting a more rounded sense of self-worth and preparing them for life beyond their athletic careers.

· Shifting Focus from Outcomes to Processes: In a results-driven world, reorienting a team's focus toward processes, effort, and growth is a monumental task. Leaders must champion a culture that values continuous improvement, learning from failures, and the journey as much as the destination. This shift not only enhances performance but also contributes to the well-being and satisfaction of athletes.

Addressing these adaptive challenges requires a leadership approach that is flexible, empathetic, and responsive. All these challenges take a lot of people working together in order to make progress. It involves fostering a culture of learning, encouraging experimentation, and facilitating difficult, yet healthy, conversations. These things might be a book in itself. Leaders must be willing to question deeply held beliefs, to listen more than they speak, and to co-create solutions with those they lead. In doing so, they not only tackle the immediate challenges but also build the adaptive capacity of their organizations or teams to face future uncertainties with confidence and resilience.

[1] Heifetz, Ronald A., and Marty Linsky. Leadership on the Line: Staying Alive through the Dangers of Change, 2. Harvard Business Review Press, 2017.

Check out our book!

Things That Are Making Us Think

You can’t be upset by predictable situations. Have a plan and respond.

This is a learning competition, not an athletic competition. (John Kessell, USA Volleyball)